Al Snow on Sabu: “And with him goes a piece of the business that we’ll never get back”

Snow reflects on the loss of a legend–and friend

Extra Mustard is a weekly column looking at the highs and lows–and everything in between–in combat sports and beyond.

The death of Sabu rips away a piece from wrestling’s past

Given the chance, Sabu would have wrestled again.

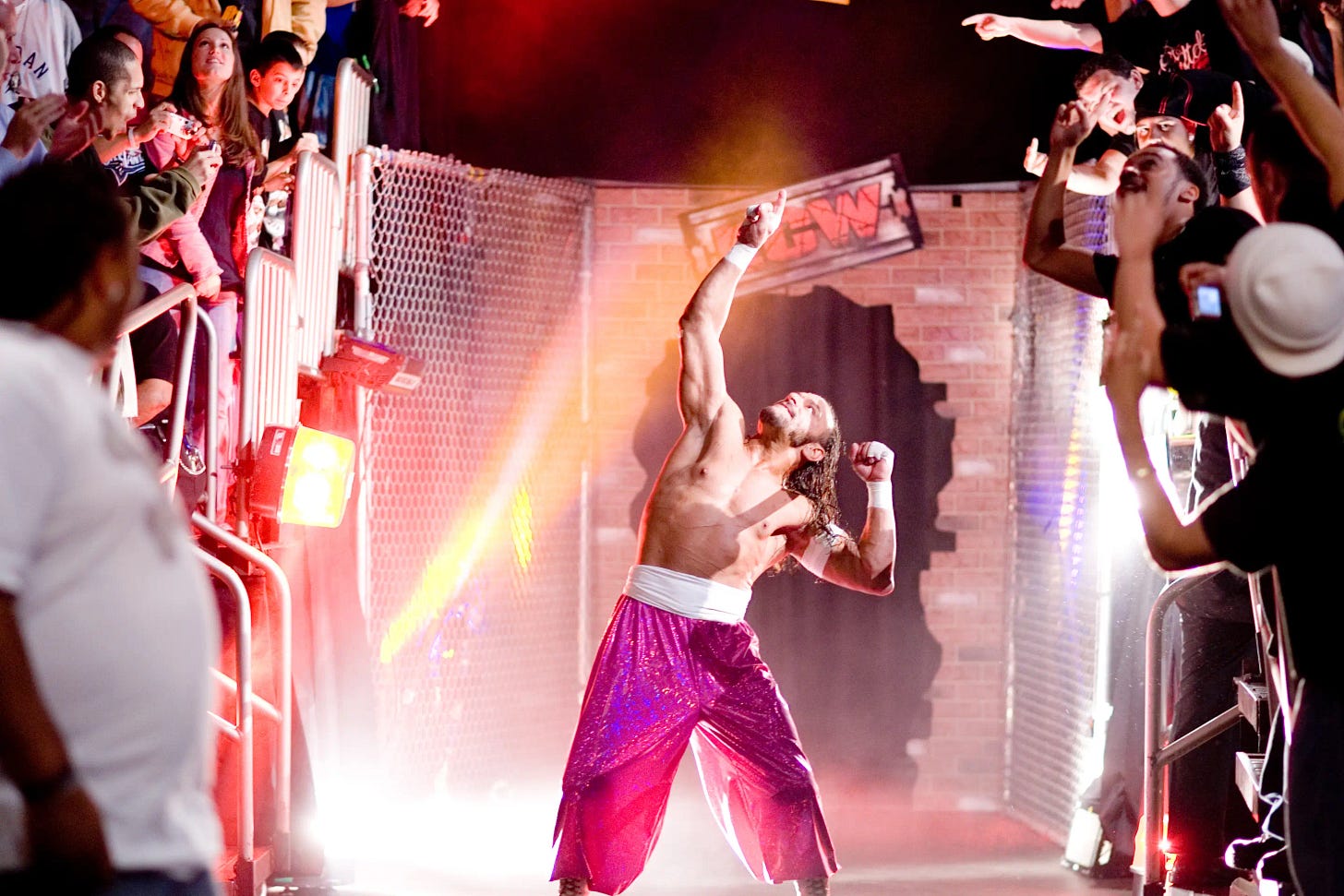

At the age of 611, Sabu was in the ring less than a month before his death. He wrestled Joey Janela in a no rope barbed wire affair on April 18 that was every bit as gruesome as it sounds. Filled with unpredictability, the match went to extreme lengths to entertain the crowd–exactly how Sabu wanted it.

No longer possessing the nimble athleticism that allowed him to soar through the air or the ruggedness to absorb intense blows, Sabu showed his age. But whether or not he knew the end was coming–the cause of death has not been revealed–Sabu finished on his own terms.

“Sabu lived the business,” said Al Snow, whose friendship with Sabu spanned five different decades. “He was my friend. We broke in very similarly and not too far apart from each other. Sabu didn’t get smartened up until his uncle–The Sheik–decided the time was right, and there was a reverence for that–the kind of which doesn’t exist anymore.

“Sheik didn’t make it easy for Sabu, and Sabu took a great amount of love in carrying his uncle’s name. It wasn’t something he did on the side. This was his life.”

Terry Brunk is the man who brought Sabu to life, and it was PWInsider’s Mike Johnson who broke the news about his death. Johnson wouldn’t be covering professional wrestling if not for his experience as a fan of Sabu during his career-altering run in Extreme Championship Wrestling, so there was a tenderness to the news of Sabu’s death being delivered by someone who lived and breathed ECW.

Sabu was a larger-than-life character who could not be tamed. And he did it with flair, redefining an ancient genre with a death-defying brilliance.

As for why Brunk was still performing in the ring, the answer is straightforward: he was Sabu. This is an instance of the man becoming the artist. Brunk merely filled in the gaps when Sabu wasn’t in the ring.

“I remember running my school in Lima, Ohio in the early 90’s, and we were on the phone,” recalled Snow. “I was referring to him as Terry, and he said no, my name is Sabu. And I remember saying, ‘We’re on the phone, Terry, no one else can hear us.’ He kept reminding me that his name was Sabu. From there forward, all I’ve ever called him is Sabu.”

Ever since the loss of his partner Melissa Coates, who went by The Genie in wrestling, in 2021, multiple people shared Brunk was heartbroken–and never fully recovered from the loss. That sadness vanished when Sabu stepped back into the ring, with the pain from a career full of brutal bumps altogether different from the burden that reality can carry.

Wrestling fans of a certain age can still hear Paul Heyman proclaiming Sabu to be the most homicidal, genocidal, and suicidal wrestler on the planet. It was more than a promotional ploy–Sabu was different. His highlight reel inspired a generation of fans to watch ECW. Then the rarest sight occurred: Sabu proved he was even better than the hype.

The colorful attire, the scars all over his body, and his ability to fly were all part of the package. Sabu was a trailblazer, a man who forcefully brought wrestling in a new direction. And that extended even deeper than deathmatches and introducing tables into his matches.

“Sabu was completely different from everyone else,” said Snow. “He was unique, he was different. That’s what pro wrestling is all about. He stood out. There was only one Sabu–and you couldn’t find anyone to duplicate him.

“He was a testament to his uncle, The Sheik, who was unique in this terrifying way. Breaking into the business, I did not want to be put into the ring with the original Sheik. Sabu loved that old-school thinking of wrestling, and he doesn’t get enough credit for his genuine love for the business.”

Part of the last generation of wrestlers from the territory days, Sabu represents the last of a dying breed. Best known for his work in ECW, Sabu also had runs all over the world, including WCW and WWE. Although he did deliver some magnificent moments (invading Monday Night Raw in 1997, his matches nearly a decade later against Rey Mysterio and John Cena), Sabu is not defined for his work in either of those companies. Post-ECW, he always seemed to fit better when he worked independently, which, again, reflected how he was part of a prior generation, one that differed dramatically from what became wrestling’s standard operating procedure.

“At times, like a lot of us, he could be his own worst enemy,” said Snow. “He wanted to emulate his uncle, but his uncle was successful in a very different era. His uncle was the owner of a massive money-making territory, and lots of talent wanted to come in work–the Funks, Dusty Rhodes, go on down the list. So when The Sheik traveled and didn’t want to do something, he could get away with it. Unfortunately, Sabu adopted a lot of those same business practices.

“Sabu didn’t compromise. That cost him opportunities. But, to his credit, he was so unique and so good that he remained this major attraction.”

Snow will hold on to the memory of Sabu as a wrestler. He’ll also cherish the memories of their friendship.

“Sabu and Chris Candido, they both helped a lot of guys in their careers,” said Snow. “Those are two people who’d take money out of their own pockets to give to guys who were getting ripped off or not paid. They looked out for others.”

Cut from a similar cloth, Snow and Sabu’s bond only strengthened throughout the years. Whenever they saw each other, it was as if no time had passed–other than the always-changing world around them.

“I’m really sad to lose my friend,” said Snow. “He’s one I’ll really miss. And with him goes a piece of the business that we’ll never get back.”

As somber as Snow was discussing the loss of Sabu, the mood lightened when entertaining the question of whether Sabu–had he not passed away–would have continued wrestling.

“Sabu always thought he had one more match in him,” said Snow. “He was addicted to this.”

WWE noted that he was 60, while The New York Times reported 61. In classic pro wrestling form, his actual birth year remains unknown.